Aswad Thomas, who is booked to speak at the Two Days in May Conference on Victim Assistance, tells a story about two young men of color who come from the same poor neighborhood.

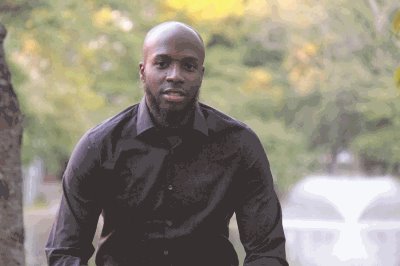

One is Thomas himself.

Of the men in Thomas’ family, including first cousins, five have been shot and seven have been incarcerated.

“They were my nontraditional role models — individuals who I did not want to follow in their footsteps,” the 36-year-old said in a phone interview.

So Thomas focused on school and basketball, becoming the first member of his family to go to college. He graduated with honors in 2009 with a business degree from Elms College in Chicopee, Massachusetts.

A point guard on the basketball team, he also led the school to its first berth and first victory in the NCAA’s Division III tournament. “Playing basketball wasn’t just a sport,” he said. “It was the only outlet for me to really escape from this community where I was surrounded by violence, poverty, drugs.”

The second man in Thomas’ story shot him twice in the back.

The attack occurred in 2009, three weeks before Thomas was set to travel to the Netherlands to sign with a pro basketball club.

The shooter grew up in the same neighborhood that Thomas did in the Connecticut capital of Hartford. He also has once been shot — in the face at age 14. Four years later, he and another man shot Thomas during a botched robbery at a corner store.

The story illustrates what Thomas calls the cycle of violence.

“He walked around my community for years angry, depressed, stressed and didn’t get help,” Thomas recalled. “I honestly feel that, as a result of his unaddressed trauma, I became a victim of gun violence.

“I think about, what if, when he became a victim, he had gotten all the support he needed to heal? Maybe I would be overseas playing basketball to this day, making a lot of money and living out my dream.”

28th annual conference: “Hidden Victims, Hidden Crime”

28th annual conference: “Hidden Victims, Hidden Crime”

When: May 20-21

Where: Greater Columbus Convention Center

Details: www.OhioAttorneyGeneral.gov/TDIM

Instead, after leaving the hospital, Thomas relearned to walk and went on to earn a master’s degree in social work from the University of Connecticut. He’s married, lives in Atlanta and is managing director of Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice, through which he helps victims push for more support and a bigger role in the criminal justice system.

Too few victims and their families get the help they need to heal, Thomas said. That can lead to housing instability, drug use, revictimization and even criminal acts.

But addressing trauma can help crime victims live better lives and prevent more crime from happening, Thomas said. Unfortunately, many victims don’t even realize support services are available.

“I know that, as a college athlete, as someone who was known in the community, I got no support after I became a victim of gun violence, no help from victim services in the community,” he said. “Law enforcement came to visit several times — not one time did they ask if I needed any help. They didn’t tell me there was a victim advocate in their department or that there was victim’s compensation.”

That lack of support continued a pattern. In 1993, when Thomas was 10 and living in Highland Park, Michigan, his best friend, Reubin Elder, was killed — the random victim of a drive-by shooting. Thomas and his friends, he said, returned to school the next Monday as if nothing had happened.

“There weren’t any counselors at the school,” he said. “We didn’t host an assembly to tell all the kids what happened. Our families didn’t talk about it.”

Just as troubling, Thomas said, is how little the situation has changed since then.

“My story is not unique. My story is very common to so many victims of crime, primarily in marginalized communities — communities of color.”

And not just in Michigan and Connecticut.

“In the state of Ohio, there are communities that don’t have any counseling services for victims, especially for victims of gun violence,” Thomas said.

Police often pass out materials spelling out victims’ rights and explaining how to apply for compensation, he said.

“Law enforcement is in the field and often doing a great job,” Thomas said. “But on that night or that day that you became a victim, or that a loved one is harmed, you don’t even remember that packet.”

Which, he said, reinforces the importance of follow-up.

He also pointed out that Ohio prohibits crime victims convicted of a felony within the previous decade from receiving compensation. The family of such a victim also is disqualified.

State law, then, would prevent a mother from receiving financial help to bury her adult child if that child had been convicted of, say, felony drug possession yet was killed years later in a random shooting.

A mother also would be denied help to bury her child if she has a felony conviction.

“Stopping the cycles of crime in our communities means stopping the cycle of trauma,” Thomas said. “To do that, we must expand our thinking about who crime victims are and we must invest in things like mental health treatment, more healing, more trauma-recovery services.

“We need more partnerships between law enforcement and community-based organizations that already have the trust of our communities. They’re the people who can reach out and make a difference, especially if they get more resources.”

These days, Thomas considers himself lucky to be alive. He has new dreams – to create a national network of support groups for young male victims of gun violence and to help stop the cycle of violence.

“I’m gonna get there,” he said.

Two Days in May featured speakers

- As attorney general, Dave Yost focuses on protecting the unprotected. “Few people fit that definition more than crime victims,” he said.

- Aswad Thomas is managing director of Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice at Alliance for Safety and Justice. He focuses on crime survivors, including young men of color, and helping them be heard.

- Steven L. Procopio, a social worker and public health consultant, has worked with HIV patients, the homeless and youths who suffered complex trauma. He now focuses on helping males of all ages recover from childhood sexual abuse and exploitation.

- Dr. Gail Stern is an author and co-founder of Catharsis Productions, which provides sexual-violence prevention education to colleges, corporations and the military. She creates education programs fueled by research and her background in standup comedy to confront challenging cultural issues.