It’s the ultimate question for investigators who have exhausted all other means of identifying skeletal remains: What did this person look like?

Thanks to advances in technology and a partnership between the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation and The Ohio State University, that question might be easier to answer in the future.

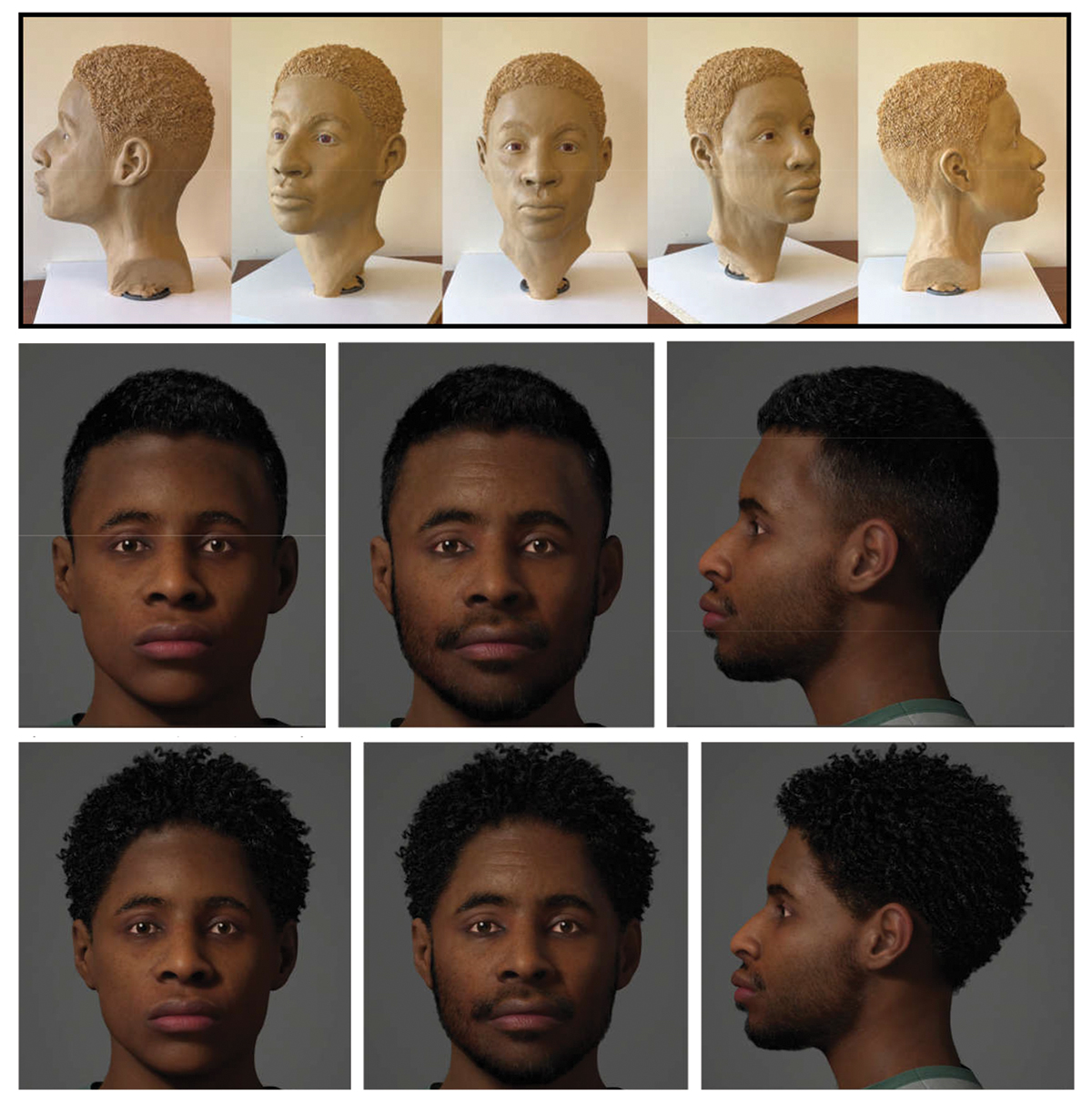

Until fairly recently, 3D facial reconstruction at BCI was essentially limited to building a clay bust based on a CT scan of the skull and an anthropological analysis to gauge the person’s age, sex, ancestry and unique anatomical features.

But a clay bust has inherent limitations because it necessitates a certain amount of guesswork for such details as the color of the eyes, hair and skin; hairstyle; facial hair; shape of the lips; the amount and location of wrinkles; and the amount of fat.

Imagine how much more helpful it would be if, in addition to a clay model, the public could view the head as photo-realistic digital images — composite views that show different skin tones, hairstyles and other attributes at different stages of aging, and from multiple angles.

That’s exactly what BCI was able to provide to Stark County Sheriff George T. Maier and County Coroner Ron Rusnak in September to aid their efforts in identifying two sets of human remains discovered in Canton nearly 20 years apart.

BCI’s ability to provide a variety of digital depictions of the decedents’ faces represents a significant advance and brings new hope for future unidentified-remains cases in Ohio. More immediately, however, it means the public will get a far better idea of what the two Stark County John Does might have looked like, thereby increasing the chances that someone will be able to assist in identification.

The addition of photo-realistic digital composites as part of BCI’s facial reconstruction process came about because of an evolving partnership that criminal analyst Samantha Molnar developed with Ohio State. It began soon after Molnar took on the additional role of forensic artist in 2015.

To make a clay bust, she first needed a CT scan of the skull she was working with. Using the digital data from the scan, she could then make a plastic model of the skull using a 3D printer. With the plastic model in hand, she could apply the clay to create the bust, adjusting for physical traits determined by an anthropological analysis of the skull.

The CT scans would need to be done at a hospital. For the 3D printer, she turned to Ohio State, which offered its services free. But the time involved in printing the 3D model could take several days, largely because of the huge amount of data in the CT scans.

A turning point came in 2019, when Molnar was working on a Jane Doe case out of Cincinnati. For whatever reason, the 3D printer could not process the CT data of the woman’s skull. A colleague at Ohio State suggested another way: Instead of a CT scan, why not use photogrammetry to acquire the data needed to make the 3D model? It worked so well that Molnar has never gone back to CTs.

Photogrammetry is a technique that renders a 3D digital image of an object — in this case, a skull — based on a series of overlapping photographs taken from numerous vantage points. In 2019, to get those photos, Ohio State’s Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD) used a connected array of multiple cameras that took hundreds of shots as the skull slowly turned on a revolving platter.

The resulting data was far less complex than a CT scan, thereby shortening the time needed to print a 3D model. But the overall process remained lengthy.

Thankfully, photogrammetry has advanced considerably since then. Today, Molnar can take 50 to 60 photos of a skull with her iPhone, email them to ACCAD and have a 3D model printed the same day.

Another turning point came two years later, in 2021. Molnar was asked by the Stark County Coroner’s Office to create a bust of a white male whose remains were found in Canton the year before. When the bust failed to produce any leads from the public, Stark County officials came knocking again. Could she re-sculpt the bust with longer hair and add facial hair, as the man might have looked if he were homeless?

It just wasn’t practical, given the time involved.

“The thing that’s limiting with a clay model is once it’s done, it’s done,” Molnar said. You’re kind of locked in.”

About this time, her colleagues at Ohio State became aware of her frustration and introduced her to a graduate student who was familiar with software that could give Molnar the flexibility she was looking for.

Coincidentally, she also had recently received another skull from Stark County, that of a black male whose remains were found in Canton in December 2001.

So now she was working on busts for two Stark County John Does, and the software that she was about to explore — MetaHuman — would shine new light on both men.

MetaHuman was developed with the gaming community in mind and allows players to apply a wide range of facial features and skin tones to the avatars they create.

Molnar knew she was on to something.

Working with her Ohio State colleagues, she could take photos of the clay bust she had built, upload them into MetaHuman, and generate the diverse combination of faces that Stark County officials had requested. And she would do the same with the second John Doe.

“The advantage of the new technology that we’re implementing through Ohio State is that it allows us to quickly edit the digital image to change features,” Molnar said. “So, if somebody calls in a tip and asks to see the face with lighter skin or the head with a different hairstyle, we’re able to accomplish that much more easily than we could have in the past.”

The technology isn’t there yet, but Molnar can envision a time when digital busts from unidentified-remains cases might be posted on a website that allows the viewer to change facial features just by clicking on the image.

“A public interface could create more publicity and generate more leads in these cases,” she said. “I think the idea will eventually gain traction.”