Investigators spent years searching for a suspect after CODIS linked 3 cold-case killings through DNA left at crime scenes

A

familial DNA test rarely used in Ohio led to the arrest of Samuel W. Legg III, a former truck driver suspected of killing at least three women decades ago — and maybe his stepdaughter.

“It’s fair to call him a serial killer,” Attorney General Dave Yost said in February while announcing Legg’s arrest.

The former northeastern Ohio resident, 50, who was extradited to Medina County from Arizona, is being held on a $1 million bond in the 1997 rape of a 17-year-old. He also has been indicted in the 1992 killing of a woman in Mahoning County; other indictments are being prepared.

Diane Gehres, technical leader of the Combined DNA Index System at the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation, said CODIS first linked two of the crime scenes — a homicide in 1996 in Wood County and one the next year in Illinois — in 2006, when the system found the same DNA logged from both.

The Mahoning County homicide was added to the grim list in 2012.

“We knew the DNA was a male’s; we just didn’t know who it belonged to,” said Lori L. Braunschweiger, a criminal intelligence analyst who has worked these cold cases since 2012, the year she joined BCI. “So we were looking for other victims to give us more investigative information that I could run intel on.”

She and BCI Forensic Scientists Steve Wiechman, Stacy Violi, Erika Jimenez and others spent six years developing suspects and running their DNA, reading cold-case reports from throughout Ohio and the nation, and contacting police departments regarding unlogged evidence.

Until recently, though, they kept striking out.

CODIS and familial DNA

Ohio joined CODIS, a national DNA database supported by the FBI, in the late 1990s. Nowadays, every adult arrested in or convicted of a felony is supposed to be swabbed for addition to the system, as is any juvenile convicted of a crime that would be a felony if he or she were an adult.

“About 4,000 arrestees and convicted offenders are added to CODIS per month,” Gehres said.

DNA profiles from the scenes of crimes, both solved and unsolved, also are uploaded.

Every night, CODIS searches for matches, be they between crime scenes or between an offender and a crime scene. When the system finds a match, BCI sends a “hit letter” to the appropriate law enforcement agency.

“About 250 a month go out,” Gehres said.

Legg’s DNA was not logged in CODIS because he had not been arrested in or convicted of a felony since collecting began.

Still, there was a hint of him in the system.

Important note

The more DNA in CODIS, the more leads the system and familial DNA testing can provide. Please ensure your agency is collecting DNA from everyone it should be.

Familial DNA searches are used only on cases in which there is a public safety issue and all investigative leads have been exhausted. There is a formal request and approval process. For more information, contact CODIS@ohioattorneygeneral.gov.

BCI turned to a tool that mines CODIS to find familial DNA, or DNA so similar to the unknown offender’s that it might come from a parent, child or sibling. The software, developed by the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth, has been used just seven times in Ohio, partly because it can lead to an expensive process to follow leads.

For that follow-up, scientists must have more than the DNA profile typically collected for CODIS.

The standard profile tracks the same highly variable sections of DNA in every person, autosomal chromosomes. Every person has 22 pairs of those — one set from your mother and one from your father.

The 23rd chromosome people have consists of a pair of sex chromosomes: X if you’re female and Y if you’re male. Every man’s 23rd chromosome exactly matches his father’s, paternal grandfather’s and those of any brothers and sons he has. The same would be true for a woman and her corresponding female relatives.

Back to the Texas software: When it links a crime scene to near-match autosomal DNA of offenders in CODIS, scientists test both for the sex-specific DNA. At $6,000, the process is more expensive than standard DNA testing.

If scientists get a match, they know they’ve likely hit on a close genetic relative of the perpetrator.

The Legg connection

It was one of Braunschweiger’s days off, a Monday in early January, when Gehres’ office sent word that the familial DNA test had resulted in a hit on a man in CODIS. He had been convicted of an unrelated crime.

Braunschweiger and another BCI criminal intelligence analyst, Lisa Savage, went to work that night to identify directly related males.

“By the next afternoon, we had a family tree and all of the birth certificates laid out,” Braunschweiger said.

The man in CODIS has a father and two brothers, including one too young to have committed the cold-case crimes.

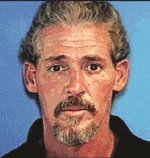

The other was Samuel Legg (shown below).

Braunschweiger’s research showed that Legg had worked jobs and lived in places that gave him the opportunity to commit the three CODIS-linked killings.

But to confirm that Legg was the man who should be charged, authorities needed his DNA. Surreptitiously trailing him in public to pick up, say, a dropped cigarette or a used plastic fork is one way to obtain DNA without alerting a person he is a suspect.

But Legg, who has neurosyphilis and schizophrenia, was living in a group home in Arizona, so finding him in public conveniently smoking or eating would be tough.

BCI needed another route to confirm that his DNA matched to the crime scenes.

Braunschweiger went back to searching for cold cases with similar MOs, and Forensic Scientist Becca Salzer started to research whether Legg had been a suspect in any case that didn’t result in charges.

On the same day, both found something.

Braunschweiger came across a 29-year-old cold case from Elyria in which a 14-year-old cheerleader had been killed. Legg was the girl’s stepfather.

Salzer found the rape in Medina, a case in which Legg had been accused but never charged. When police questioned him in 1997, he claimed the sex was consensual.

The 17-year-old girl had gotten a rape kit completed, pieces of which the Medina police still had. DNA from those pieces — which Legg had confirmed would be his during questioning — matched the unknown cold-case killer’s in CODIS.

The discovery allowed Medina police to secure a search warrant to swab Legg for DNA. The sample confirmed the match, and Legg was extradited — all within a month of the familial DNA test.

The speed “was so crazy after working on these cases all of these years,” Braunschweiger said.

And another upside to the BCI team’s work, she said, was the resubmitting of old unsolved-homicide evidence from agencies throughout Ohio and in other states.

“Quite a few of them came back with DNA profiles, from places like Florida and California, Colorado.”

Which means more cases have a better chance of being solved.

Familial DNA successes

The Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation has used the familial DNA testing process on seven occasions. The tests resulted in a suspect three times, including the Samuel Legg cases. Here are the other two:

In 2016, a man abducted a 6-year-old girl from her bedroom in Cleveland. He sexually assaulted the girl and dropped her off on a street corner. CODIS linked DNA from the crime to another attempted abduction: that of a 10-year-old in Elyria a few months earlier. That girl had gotten away.

After the familial DNA process was used in Ohio for the first time,

Justin A. Christian (shown above) was arrested in December of that year. He pleaded guilty to kidnapping, rape, gross sexual imposition and burglary in both cases and is serving a 35-year prison sentence.

In the summer of 2018, two stranger rapes on a Deerfield bike trail in Portage County had the community on edge. Another rape in a Mahoning County park, on Sept. 4, 2018, was linked to the same perpetrator.

Three days later — within 24 hours of BCI’s familial DNA test — authorities arrested

Shawn Michael Wendling (shown above), a Pennsylvania man who worked in Ohio. On March 1, he pleaded guilty to two counts of rape, two counts of kidnapping and one count of felonious assault in Portage County, receiving 30 years in prison. His case in Mahoning County is still pending.